Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a general term that covers all structural problems with the heart that are present from birth. Hearts can have incomplete or missing parts, leaky valves, holes between chambers or are simply put together the wrong way. Some CHDs are simple and don’t need treatment, while others need serious intervention.

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)

CHDs are the most common serious birth abnormality in Aotearoa New Zealand.

How are congenital heart conditions diagnosed?

Some CHDs can be detected pre-birth by a Level II ultrasound or by a foetal echocardiogram. After birth, a congenital heart condition is often first detected when the doctor hears an abnormal heart sound or heart murmur when listening to the heart. Depending on the type of murmur, the doctor may order further testing such as an echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or other diagnostic testing.

What are common signs and symptoms?

The warning signs in babies and children include:

- A heart murmur or abnormal heart sound

- Cyanosis (a bluish tint to the skin, fingernails and/or lips)

- Fast breathing, poor feeding

- Poor weight gain

- An inability to exercise and excessive sweating

What are the most common CHDs?

While there are over 40 different congenital heart conditions, there are a few that are the most common. These are:

Aortic Valve Disease (AVD)

Aortic Valve Disease is a condition where the valve between the heart’s lower left chamber (left ventricle) and the main artery connecting the heart and the body (aorta) doesn’t work properly.

There are two common types of AVD:

Aortic valve stenosis: This occurs when the flaps of the aortic valve stiffen or fuse together, narrowing the valve’s opening and blocking the flow of blood from the heart to the body.

Aortic valve regurgitation: This is when the aortic valve doesn’t close properly, allowing blood to flow back into the left ventricle.

As well as being a congenital defect that’s present at birth, AVD is sometimes the result of infections. It can also develop in older adults who develop high blood pressure or heart injuries like heart attacks.

Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

As a baby develops in the womb, its heart has openings in the wall dividing the organ’s upper chambers (atria). These usually close during pregnancy, or just after birth. But sometimes they don’t, and the remaining hole is called an Atrial Septal Defect.

Sometimes, these holes close without treatment. But when they don’t, the hole results in more blood flowing through to the lungs. This can cause damage to the lung’s blood vessels, which can cause problems in adulthood like high blood pressure, heart failure, abnormal heartbeat and greater risk of stroke.

Atrio-Ventricular Septal Defect (ASVD)

With AVSD, holes between the right and left sides of the heart means that blood flows where it shouldn’t. Often, the valves which control the blood flow are defective.

This results in blood with low oxygen levels, and extra blood flowing to the lungs. The heart and lungs are forced to work harder, which can lead to congestive heart failure.

In most cases of AVSD, surgery is needed in the first six months of a child’s life.

Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA)

Also known as aortic narrowing, CoA means the heart has to pump extra hard to force blood through the narrow part of the aorta.

While the narrowing is usually found near the ductus arteriosus blood vessel, it can affect any part of the aorta.

CoA is usually identified at birth, although it depends on how much the aorta has narrowed as to how likely it is to be detected. Sometimes it’s not discovered until adulthood.

CoA symptoms range from mild to severe. Babies on the severe end will generally start showing symptoms shortly after birth: pale skin, sweating and breathing difficulties. After infancy, symptoms include high blood pressure, headaches, muscle weakness, leg cramps, nosebleeds and chest pain.

While treatment has a good success rate, CoA generally results in lifelong monitoring.

Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease (CCHD)

A few conditions fall under the CCHD umbrella, with each resulting in low blood oxygen levels causing breathing difficulties, and giving lips, toes, palms or fingers a bluish tinge known as cyanosis.

Genetics can play a part in CCHD. That could mean a family history of congenital heart disease, or an accompanying condition like Down Syndrome.

Sometimes, external factors during pregnancy can cause CCHD. These include drug use, toxic chemical exposure, infections or poorly controlled gestational diabetes.

Find out more about cyanotic diseases here.

Mitral Valve Defects (MVD)

In this condition, a fault in the mitral valve causes blood to flow back into the heart’s left atrium and means the heart can’t pump enough blood out of its left ventricular chamber. This back flow is known as mitral valve regurgitation.

Mitral valve stenosis – when the mitral valve is narrowed, blocking blood flow to the left ventricle – is often caused by rheumatic fever, a complication of a strep infection. However, in some cases, mitral stenosis is congenital.

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a common congenital heart defect. The valve is abnormally formed in such a way that the two valve flaps bend backwards into the left atrium as the heart beats.

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)

In a growing fetus, the ductus arteriosus blood vessel connects the aorta and the pulmonary artery. The tube normally closes around the time of birth. However, when it doesn’t, it results in blood flow to the lungs, making the heart and lungs work harder.

However, if the tube is small and not impacting the way these organs work, intervention might not be necessary.

Find out more about PDA here.

Pulmonary Artresia (PA)

PA is a defect of the pulmonary valve, which controls the blood flow from the heart’s lower right chamber to the main pulmonary artery (the blood vessel between the heart and the lungs).

When this valve doesn’t form properly, blood is prevented flowing from the heart’s right ventricle to the lungs.

Babies born with PA will need medication to keep their ductus arteriosus open, helping with blood flow to the lungs until the valve can be repaired.

Find out more about PA here.

Pulmonary (Valve) Stenosis (PVS)

Pulmonary (valve) stenosis is a condition caused by blockage to blood flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery. This blockage (obstruction) is caused by narrowing (stenosis) at one or more points from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery.

Children with pulmonary valvar stenosis are usually symptom free and in normal health. A heart murmur is the most common sign found by a doctor that shows that a valve problem may be present.

A newborn with critical pulmonary stenosis is an emergency that needs immediate treatment.

Pulmonary Valve Disease (PVD)

When the pulmonary valve (located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery) doesn’t work properly, it can affect the flow of blood from your heart to your lungs. The treatment for pulmonary valve disease depends on the type and severity of the condition.

Single Ventricle Pathology (SVP)

If a lower ventricle fails to develop, the heart is left with just one blood-pumping chamber. This means less oxygen-rich blood flowing around the body.

Some children with single ventricles will have other heart defects, too. And in most, the cause is unknown. Surgery and medical intervention will be required to ensure the blood pumps around the body in the right way.

Find out more about single ventricle anomalies here and here.

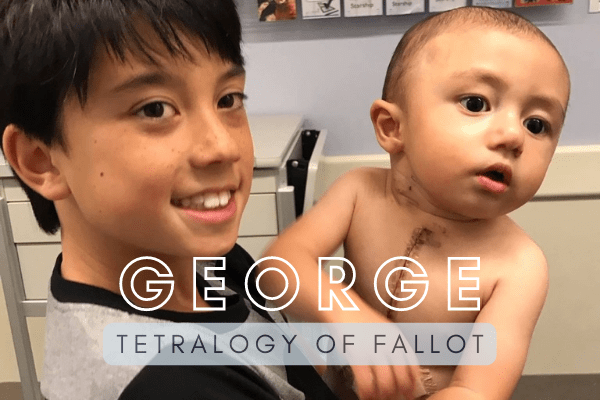

Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF)

This condition is a combination of four defects of the heart and its blood vessels:

- Ventricular septal defect: a hole in the wall between the heart’s two lower chambers (ventricles).

Pulmonary stenosis: a narrowing of the pulmonary valve, and main pulmonary artery.

Ventricular hypertrophy: when the heart’s right ventricle wall is thicker than normal.

Overriding aorta: when the aortic valve is enlarged, and seems to open from both ventricles, unlike a normal heart, which opens from the left.

In ToF, abnormal blood flow from the heart to the lungs results in blood being diverted through the ventricular septal defect to the aorta. This can cause lower blood flow and lung circulation and causes the child to appear blue.

ToF is considered severe, and a baby born with the condition will likely need surgery or other interventions shortly after birth.

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

The most common heart defect in children, VSD is formed during pregnancy, when the wall (septum) separating the heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) doesn’t form properly.

The resulting hole allows blood to pass between the left and right side of the heart. The blood is then pumped into the lungs instead of out to the body, forcing the heart and lungs to work harder.

Without repair, the defect can cause other complications like heart failure, high blood pressure in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension), irregular heart rhythms (called arrhythmia), or stroke.

Where can you find out more?

There are several resources and websites in Aotearoa New Zealand and abroad that provide a range of information relating to CHD. We recommend the following:

- Health Navigator New Zealand – Congenital Heart Disease (NZ)

- Starship Green Lane Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Service (NZ)

- Congenital Heart Alliance of Australia and New Zealand (CHAANZ)

- Liggins Institute – Antenatal Scans Save Heart Disease Babies’ Lives (NZ)

- Johns Hopkins University’s Cove Point Foundation – Congenital Heart Resource Center (US)

- Cincinnati Children’s Heart Encyclopedia (US)

- Cincinnati Children’s Heartpedia Mobile App (iOS, Android)

- Adult Congenital Heart Association (US)

- Children’s Heart Federation – Heart Conditions (UK)